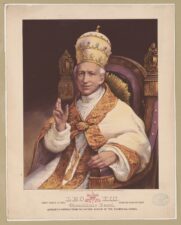

Image: Library of Congress

I suspect he might have. The papacy is an extremely important office, and any successful pope will carefully consider the ramifications of his words and actions before he does anything. (Pope Francis is no exception.)

Even if he didn’t, the encyclical and its successors launched new lines of thought for the Church. Leo XIII was the first pope elected after the Rome was occupied and annexed by Italy, meaning that he received a leadership office that had no temporal power. This was only eight years after the capture of Rome, but his reign came on the heels of one of the most successful popes in history, Pope St. Pius IX, who had presided over the First Vatican Council, infallibly defined a new Marian doctrine, and reformed the entire episcopate. These events served to revitalize and reorient the Church, encouraging more participation on the part of the laity.

The 1890s, of course, were the height of the Second Industrial Revolution, and particularly since he had no temporal power, Leo XIII would have had plenty of reason to pay more than the usual attention to what his subjects were talking about. It’s no surprise, then, that he would have released an encyclical about labor and work; Rerum Novarum’s English title is usually rendered as “On the Condition of Labor.” It was considered groundbreaking even its own time, and it also sparked the beginning of (to date) nearly a hundred forty years of doctrinal development about human dignity, human society, and social justice.

One striking aspect of the encyclical was that the pope didn’t “take sides” for or against any particular economic model. Instead, as the USCCB notes (PDF link):

Leo XIII criticizes both capitalism for its tendency toward greed, concentration of wealth, and mistreatment of workers, as well as socialism, for what he understood as a rejection of private property and an under-emphasis on the dignity of each individual person.

This was the beginning of what’s now collectively known as Catholic Social Teaching, which has been characterized as “the Church’s best-kept secret.”

It’s primarily taught through seminars with voluntary attendance, although I’ve heard several homilies that were clearly rooted one or more aspects of it. In the United States, it also flies directly in the face of the traditional two-party political system; it’s not easy to classify or quantify and it’s paradoxical. There are also still many Catholics who (incorrectly) believe it’s an optional part of the faith, and more who believe that its requirements are more than satisfied via organizations such as Catholic Charities. As such, they reason, they don’t even need to know that much about it.

I did, though; Catholic Social Teaching played a major role in my reversion in the early 2000s. I had long had difficulty figuring out my own political typology, and based on my American worldview I thought this meant there was something “wrong” with me. Yet when I started reading outlines of it, I found myself agreeing to its assertions again and again. I realized that there is a way to be political and Catholic, one that is sanctioned (and even encouraged) by the Church itself.

As it happened, the parish I was attending at the time I was Confirmed also sponsored a JustFaith program that began with Scripture and spirituality, and gradually worked outward toward notions of solidarity, justice, and action. The program gave me the chance to delve even deeper into this quiet treasure I’d discovered, and to formulate and articulate my own opinions about the nature of human society. It wasn’t always easy to ponder these things, but both my faith and my opinions are stronger for having worked through these issues. So is the way I live my life.

In the end, isn’t that one of the purposes of religion: to define a worldview, establish a particular way of living, and ultimately to become a part of something larger than yourself?

Toward the end of the nine-month program, one of the other participants asked the question: “but what can we do about all this?” It engendered a lively discussion that I’ve never forgotten, during which I learned about the doctrine of the economy of salvation, which states that every Catholic bears a duty to help order our world toward God’s plan of salvation. An essential part of the teaching is that an individual Catholic does not need to do “big things” or “make a difference to everyone.” Even the smallest act, if it contributes toward that economy, is a good thing.

I haven’t been able to take public action as much as I’ve liked over the years, but one thing I can do is write. Even of only one person is moved by my words, I will have accomplished my purpose. That’s one of the reasons I re-started this blog this past summer, and I plan to continue revisiting this topic.

The next post will give a broad outline of Catholic Social Teaching, which can be divided into a number of different themes.

Comments