Image: -ted

Farid, who by then was in his fifties or sixties, was soft-spoken and rarely met anyone’s eyes, but he was aware of everything that went on in that office. He was also creative, often using his fingernails to whittle little statues out of used matchsticks or discarded pencils. He was polite, and once he got to know someone, was often willing to initiate casual conversations.

All of us at that office became used to his presence, staying slightly out of the way, mop or broom in his hands. He sometimes talked a little about prison life; one of his favorite hobbies was lifting weights, and he loved watching seasonal changes as they affected the exercise yard.

For the most part, Farid was harmless. He never talked about his past or why he was in prison, but it was clear he had been for a long time: one time, when I bought a late-model used car, he exclaimed that it must have cost a thousand dollars or more. In his mind, that was an incredible amount of money and he meant the statement as a compliment. But it was also telling, as I hadn’t paid a thousand dollars for that car. I’d paid ten thousand, which was a reasonable price for a good used vehicle at the time.

I never told him how far off he was. It wasn’t that kind of relationship. But I always appreciated the little things he did for us every day, and thanked him for those, and his response was a shy smile and a willingness to continue.

Some months after I began working in that position, I was asked to begin helping out in the file room. Inmates were not permitted in this room because it contained their prison files. One day, out of curiosity, I pulled Farid’s file.

My jaw dropped.

In the late 1960s, while high on illicit drugs, Farid had attempted to buy some more. His source either couldn’t or wouldn’t provide them. In response, he dragged the man out behind a convenience store, kicked and punched him until he was on the ground, and then smashed his head in with a cinder block. The files contained no pictures, but it’s not difficult to imagine what the witnesses must have seen. Farid, who was still high when he was arrested, made no attempt to hide what he was doing or had done.

His trial was very short, and could only have had one outcome: he was convicted of first-degree murder, as the killing had been done as a part of another felony. Farid was sentenced to death, and a copy of that decree was in the file. My blood ran cold as I read it. It specified the means of execution (gassing) and ended with a set-out, solemn proclamation: “…and may God have mercy on his soul.”

Farid’s sentence had been commuted to life as a result of the the 1972 Furman v. Georgia decision, and the state had elected not to re-do the sentencing portion of the trial. Over time, he’d worked his way up the various levels of incarceration, finally making it to minimum security around 1990. It wasn’t linear; there were aberrations, and he’d had multiple infractions (mostly for fighting). He’d been denied parole several times; and program managers, noting various details of his case, had identified him as very likely to relapse into addiction and commit another drug-related crime.

By then, I’d learned the word institutionalized as it related to prison populations. Farid’s file indicated a classic case: he generally did fine as long as he was inside, but he had almost no coping skills or support networks to ever transition out. Both he and society were best served by him staying in prison, with its externally-imposed behavioral structure.

Reading that file, and comparing it with the Farid I knew, left me wondering about the death penalty in general. Before then, it hadn’t really been on my radar; I knew that some prisoners were so dangerous that they couldn’t ever be let out, and thus vaguely supported capital punishment simply as a way to conserve resources. It came as a surprise when I saw the number of appeals in Farid’s file, and that left me curious enough to do the research and learn that it’s far more expensive to execute a convicted criminal than it is to keep them in prison for the rest of their life.

I learned quickly that capital punishment proponents felt as though convicted murderers had no value to society. In Farid’s case, I couldn’t agree. Yes, he needed to stay in prison, but there was no doubt in my mind that he was a contributing member of society. Farid made $1 per day for his work, which was a lot less than any janitorial service would have charged, even then. To be sure, his contribution was small, but it was not nothing, and in terms of scale I could see why the inmate-work program was a very prudent stewardship of taxpayers’ money.

The 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church had a very clear teaching about the use of capital punishment:

Preserving the common good of society requires rendering the aggressor unable to inflict harm. For this reason, the traditional teaching of the Church has acknowledged as well-founded the right and duty of the legitimate public authority to punish malefactors by means of penalties commensurate with the gravity of the crime, not excluding, in cases of extreme gravity, the death penalty. If bloodless means are sufficient to defend human lives against an aggressor and to protect public order and the safety of persons, public authority should limit itself to such means because they better correspond to the concrete conditions of the common good and are more in conformity to the dignity of the human person.

Reading this, and thinking about Farid, got me to wondering how many inmates had successfully escaped from death row.

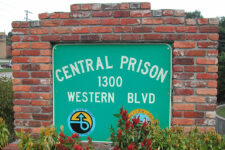

The answer, as it pertained to North Carolina’s Central Prison, was startling: zero. Every death-sentenced inmate that had ever escaped had done so from other facilities.

Clearly, at least in North Carolina, it was possible to protect society from the most violent of inmates without resorting to execution. As a Catholic, then, I could no longer support capital punishment, at least in that state. Further, as my employment with the Division of Prisons transitioned from temporary to regular and I had the opportunity to visit various institutions and functions, I could clearly see that even the inmates in Central could contribute in small ways.

This was when I began to oppose capital punishment. I still had a path forward after that, as I had a lot to learn. But the destination was set as a result of my experience with Farid. Killing him wasn’t necessary to protect society; life in prison — with its small but significant opportunities for grace, dignity, and giving back to society — was sufficient.

The still-controversial 2017 revision of the Catechism, which now explicitly states that it’s possible to protect society without resorting to capital punishment, came as no surprise to me. I’d long since figured out that that condition already existed in most places; in my mind, the revision was simply a statement of fact.

While the use of the death penalty isn’t forbidden by the Fifth Commandment, it’s also no longer needed. We as a society can, should, and must do better.